North American T-28 Trojan

| T-28 Trojan | |

|---|---|

A US Navy T-28B in 1973 | |

| General information | |

| Type | Trainer aircraft Light attack |

| Manufacturer | North American Aviation |

| Primary users | United States Air Force |

| Number built | 1,948 |

| History | |

| Manufactured | 1950–1957 |

| First flight | 24 September 1949 |

| Retired | 1994 Philippine Air Force[1] |

| Developed from | North American XSN2J |

| Developed into | AIDC T-CH-1 |

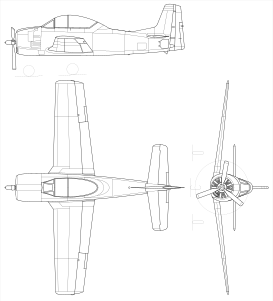

The North American Aviation T-28 Trojan is a radial-engine military trainer aircraft manufactured by North American Aviation and used by the United States Air Force and United States Navy beginning in the 1950s. Besides its use as a trainer, the T-28 was successfully employed as a counter-insurgency aircraft, primarily during the Vietnam War. It has continued in civilian use as an aerobatics and warbird performer.

Design and development

[edit]On 24 September 1949, the XT-28 (company designation NA-159) was flown for the first time, designed to replace the T-6 Texan. The T-28A arrived at the Air Proving Ground, Eglin Air Force Base, Florida, in mid-June 1950, for suitability tests as an advanced trainer by the 3200th Fighter Test Squadron, with consideration given to its transition, instrument, and gunnery capabilities.[2] Found satisfactory, a contract was issued and between 1950 and 1957, a total of 1,948 were built.

Following the T-28's withdrawal from U.S. military service, a number were remanufactured by Hamilton Aircraft into two versions called the Nomair. The first refurbished machines, designated T-28R-1 were similar to the standard T-28s they were adapted from, and were supplied to the Brazilian Navy. Later, a more ambitious conversion was undertaken as the T-28R-2, which transformed the two-seat tandem aircraft into a five-seat cabin monoplane for general aviation use. Other civil conversions of ex-military T-28As were undertaken by PacAero as the Nomad Mark I and Nomad Mark II[3]

Operational history

[edit]

After becoming adopted as a primary trainer by the USAF, the United States Navy and Marine Corps adopted it as well. Although the Air Force phased out the aircraft from primary pilot training by the early 1960s, continuing use only for limited training of special operations aircrews and for primary training of select foreign military personnel, the aircraft continued to be used as a primary trainer by the Navy (and by default, the Marine Corps and Coast Guard) well into the early 1980s.

The largest single concentration of this aircraft was employed by the U.S. Navy at Naval Air Station Whiting Field in Milton, Florida, in the training of student naval aviators. The T-28's service career in the U.S. military ended with the completion of the phase-in of the T-34C turboprop trainer. The last U.S. Navy training squadron to fly the T-28 was VT-27 "Boomers", based at Naval Air Station Corpus Christi, Texas, flying the last T-28 training flight in early 1984. The last T-28 in the Training Command, BuNo 137796, departed for Naval District Washington on 14 March 1984, in order to be displayed permanently at Naval Support Facility Anacostia, D.C.[4]

Vietnam War combat

[edit]

In 1963, a Royal Lao Air Force T-28 piloted by Lieutenant Chert Saibory, a Thai national, defected to North Vietnam. Saibory was immediately imprisoned and his aircraft was impounded. Within six months the T-28 was refurbished and commissioned into the North Vietnamese Air Force as its first fighter aircraft.[5] Lt. Saibory later trained NVAF pilot Nguyen Van Ba in the operation of the T-28, where Nguyen flew the T-28 in its first successful interception against an RVNAF C-123 Provider on 15 February 1964, earning the NVAF its first-ever aerial victory.[6] The NVAF unit that operated the T-28 in the respective military operation has later evolved into the modern Vietnam Airlines.[7]

T-28s were supplied to the Republic of Vietnam Air Force (RVNAF) in support of ARVN ground operations, seeing extensive service during the Vietnam War in RVNAF hands, as well as the Secret War in Laos. A T-28 Trojan was the first US fixed wing attack aircraft (non-transport type) lost in South Vietnam, during the Vietnam War. Capt. Robert L. Simpson, USAF, Detachment 2A, 1st Air Commando Group, and Lt. Hoa, RVNAF, were shot down by ground fire on August 28, 1962, while flying close air support. Neither crewman survived. The USAF lost 23 T-28s to all causes during the war, with the last two losses occurring in 1968.[8]

Other combat uses

[edit]T-28s were used by the CIA in the former Belgian Congo during the 1960s.[9]

The T-28B and D were the primary ground attack aircraft of Khmer Air Force in Cambodia during the war there, largely provided from the U.S. Military Equipment Delivery Team and maintained by Air America.[10] On the night of 21 January 1971, PAVN sappers managed to get close enough to destroy the majority at Pochentong airbase. Replacements were quickly shipped in. On 17 March 1973 a pilot of a T-28, said to be Capt. So Petra, a common-law husband of one of the daughters of the overthrown Prince Norodom Sihanouk, machine gunned and bombed the palace of Lon Nol in an attempt to assassinate him, killing at least 20 and wounding 35, before defecting to Khmer Rouge held lands.[11]

France's Armée de l'Air used locally re-manufactured Trojans, T-28S Fennec, for close support missions in Algeria.[12]

Nicaragua replaced its fleet of 30+ ex-Swedish P-51s with T-28s in the early 1960s,[13] with more aircraft acquired in the 1970s and 1980s.[14]

The Philippines utilized T-28s (colloquially known as "Tora-toras") during the 1989 Philippine coup attempt. The aircraft were often deployed as dive bombers by rebel forces.[citation needed]

Civilian use

[edit]AeroVironment modified and armored a T-28A to fly weather research for South Dakota School of Mines & Technology, funded by the National Science Foundation, and operated in this capacity from 1969 to 2005.[15][16] SDSM&T was planning to replace it with another modified, but more modern, former military aircraft, specifically a Fairchild Republic A-10 Thunderbolt II.[17] This plan was found to carry too many risks associated with the costly modifications required and the program was cancelled in 2018.[18]

MicroProse purchased a T-28B in 1988 for use in marketing their flight simulator video games, and named it "Miss MicroProse". USAF reserve pilot Bill Stealey would fly with games journalists for this purpose, and ran a competition called I Cheated Death with Major Bill which selected three fans to fly with him on a "stunt-filled flight lesson". The plane was later sold to a flight school in Cincinnati.[19]

Aerobatics and warbird display

[edit]Many retired T-28s were subsequently sold to private civil operators, and due to their reasonable operating costs are often found flying or displayed as warbirds today.

Variants

[edit]

- XT-28

- Prototype; two built.

- T-28A

- U.S. Air Force version with an 800 hp (597 kW) Wright R-1300-1 radial engine driving a two-bladed propeller; 1,194 built.[21][22]

- T-28B

- U.S. Navy land-based trainer version with 1,425 hp (1,063 kW) Wright R-1820-86 radial engine driving a three-bladed propeller and fitted with a belly-mounted speed brake; 489 built from new and 17 converted from T-28.[23][22]

- T-28C

- U.S. Navy version, a T-28B with shortened propeller blades and tailhook for carrier-landing training; 299 built.[22][24]

- T-28D Nomad

- T-28Bs converted for the USAF in 1962 for the counter-insurgency, reconnaissance, search and rescue, and forward air controller roles in Vietnam. Fitted with two underwing hardpoints. The later T-28D-5 had ammo pans inside the wings that could be hooked up to hardpoint-mounted gun pods for a better center of gravity and aerodynamics; 321 converted by Pacific Airmotive (Pac-Aero).

- T-28 Nomad Mark I - Wright R-1820-56S engine (1,300 hp (969 kW)).[3][25]

- T-28 Nomad Mark II - Wright R-1820-76A (1,425 hp (1,063 kW))

- T-28 Nomad Mark III - Wright R-1820-80 (1,535 hp (1,145 kW))[26]

- Fairchild AT-28D

- Attack model of the T-28D used for Close Air Support (CAS) missions by the USAF and allied Air Forces in Southeast Asia, which were nicknamed "Tangos" by their pilots.[27] It was fitted with six underwing hardpoints and the rocket-powered Stanley Yankee ejection seat;[28] 72 converted by Fairchild Hiller.

- YAT-28E

- Experimental development of the counter-insurgency T-28D. It was powered by a 2,445 hp (1,823 kW) Lycoming YT-55L-9 turboprop, and armed with two 12.7 mm (0.50 in) machine guns and up to 6,000 lb (2,700 kg) of weapons on 12 underwing hardpoints. Three prototypes were converted from T-28As by North American, with the first model flying on 15 February 1963. The project was canceled in 1965.[29]

- T-28S Fennec

- Ex-USAF T-28As converted in 1959 for use by the French Armée de l'Air, replacing the Morane-Saulnier MS.733A. It was flown by their Escadrilles d'Aviation Légère d'Appui (EALA; "Light Aviation Support Squadrons") in the counterinsurgency role in North Africa from 1959 to 1962. Fitted with an electrically powered sliding canopy, side-armor, a 1,200 hp (895 kW) Wright R-1820-97 supercharged radial engine (the model used in the B-17 bomber),[30] and four underwing hardpoints.[31] It is referred to as the "S" variant because its engine had a supercharger on it; it has also been referred to as the T-28F variant – with the "F" standing for France.[citation needed]

- For fire support missions it usually carried two double-mount 12.7 mm (0.50 in) machine gun pods (with 100 rounds per gun) and two MATRA Type 122 6 x 68 mm (2.7 in) rocket pods.[31] It could also carry on paired hardpoints a 120 kg (260 lb) HE or GP "iron" bomb, a MATRA Type 361 36 x 37 mm (1.5 in) rocket pod, a SNEB 7 x 55 mm (2.2 in) rocket pod, or a MATRA Type 13 single-rail, MATRA Type 20 or Type 21 double-rail, MATRA Type 41 quadruple-rail (2 x 2), or MATRA Type 61 or Type 63 sextuple-rail (3 x 3) SERAM T10 heavy rocket launchers.[31] Improvised napalm bombs (called bidons spéciaux, or "special cans") were created by dropping gas tanks loaded with octagel-thickened fuel inside, then later igniting or detonating the spilled fuel with white phosphorus rockets.[31]

- Total 148 airframes bought from Pacific Airmotive (Pac Aero) and modified by Sud-Aviation in France. After the war the French government offered them for sale from 1964 to 1967.[12] They sold most of them to Morocco and Argentina.[12] The Fuerza Aérea de Nicaragua (FAN) purchased four of these ex-Morocco aircraft during 1979.[citation needed] Argentina later sold some to Uruguay and Honduras.[12]

- T-28P

- T-28S Fennec aircraft sold to the Argentinian Navy as carrier-borne attack aircraft. They were given shortened propeller blades and a tailhook to allow carrier landings.[32]

- T-28R Nomair

- An attempt by Hamilton Aircraft Company of Tucson, Arizona to make a civilianized Nomad III-equivalent out of refurbished ex-USAF T-28As. It had a Wright Cyclone R-1820-80 engine to make it fast and powerful, but had to lengthen the wingspan by seven feet to reduce the stall speed to below a "street-legal" 70 knots.[26][33] The prototype flew for the first time in September 1960, and the FAA Type Certificate was received on 15 February 1962.[33] At the time, the T-28-R2 was the fastest single-engined standard category aircraft available in the United States. It had been flown to a height of 38,700 ft (11,800 m).

- T-28R-1 Nomair I

- A military trainer that had a tandem cockpit, dual instrumentation and flying controls, and hydraulically-actuated rearward-sliding canopy.[26][34] Six were sold in 1962 as carrier-landing trainers to the Brazilian Navy and were modified with a carrier arrestor hook. They were later transferred to the Brazilian Air Force.[33]

- T-28R-2 Nomair II

- Modified to have a cramped five-seater cabin (one pilot and two rows of two passengers) that opened from the port side.[26][34] Ten aircraft were modified in all; one was sold to a high-altitude photographic company.[33]

- RT-28

- Photo reconnaissance conversion for counter-insurgency use with Royal Lao Air Force. Number of conversions unknown.[35][36]

- AIDC T-CH-1

- A derivative of the T-28 developed by AIDC in Taiwan, the AIDC T-CH-1 was powered by a 1,082 kW (1,451 hp) Avco Lycoming T53-L-701 turboprop engine. Fifty aircraft were produced for the Taiwanese Air Force between March 1976 and 1981. The type has since been retired.[citation needed]

Operators

[edit]

- Argentine Air Force - 34 T-28A[37][38]

- Argentine Naval Aviation.[38] 65 ex-French Air Force T-28S Fennec aircraft.[39][40] Last nine transferred to Uruguayan naval aviation in 1980.[citation needed]

- Bolivian Air Force at least six T-28Ds.[38][39][41]

- Brazilian Navy - 18 T-28C[38]

- Air Force of the Democratic Republic of the Congo - 14 T-28C, 3 T-28B, 10 T-28D[42]

- Cuban Air Force - 10 T-28As were ordered by the Batista regime but were never delivered owing to an arms embargo,[43][44] although at least one T-28 seems to have been acquired at some stage which was put on display at a museum at Playa Girón[45][46]

- Ecuadorian Air Force - nine T-28A[38][48]

- Ethiopian Air Force - 12 T-28A and 12 T-28D[38][39][40][49]

- French Air Force - 148 T-28A airframes modified in France (1959) to make the T-28S Fennec COIN model.[40]

- Haitian Air Force - 12 ex-French Air Force[38]

- Honduran Air Force - eight former Moroccan Air Force Fennecs. One delivered, seven others impounded at Fort Lauderdale[39][40][50]

- Japanese Air Self-Defense Force - one T-28B[51][52]

- Khmer Air Force operated 47 T-28s in total in service.[38][39][40]

- Royal Lao Air Force - 55 T-28D[38][39][40][53]

- Mexican Air Force - 32 T-28A[38][40][54]

- Royal Moroccan Air Force - 25 Fennec aircraft [38][39][40][50]

- Nicaraguan Air Force - six T-28D[38][40]

- Philippine Air Force - 12 units T-28A[38][39][40][55],

,32 units T-28D[56]

- Tunisian Air Force - Fennec[38]

- United States Army[61]

- United States Air Force - 1194 T-28A, of which 360 converted to "D"[38]

- United States Navy - 489 T-28B and 299 T-28C[38]

- Uruguayan Naval Aviation - Fennec [40][62]

Surviving aircraft

[edit]

Many T-28s are on display throughout the world. In addition, a considerable number of flyable examples exist in private ownership, as the aircraft is a popular sport plane and warbird.

Argentina

[edit]- On display

- T-28A

- S/N 174112 (ex-USAF 51-3574), formerly operated by the Argentine Air Force as E-608. Preserved at the Museo Regional Inter Fuerzas, Estancia Santa Romana, San Luis.[65]

- C/N° 174333 (ex-USAF 51-3795), formerly operated by the Argentine Naval Aviation. Preserved at the Argentine Naval Aviation Museum.[66]

Australia

[edit]- On display

- T-28A

- 49-1583 - Australian Aviation Museum, Bankstown Airport, New South Wales, Australia.[67]

- T-28 Trojan 50-221 "LITTL JUGGS". Toowoomba Australia[68]

- T-28B Bu 140016, Located at Jandakot Airport in Western Australia. Owned by AOG Services and registered as VH-KAN. Imported from the US in 2014 and formerly N46984.[citation needed]

Philippines

[edit]- T-28A

- 109 - Philippine Air Force Museum. Colonel Jesus Villamor Air Base Pasay, Metro Manila[69]

- 7760 -Basilio Fernando Air Base. Lipa, Batangas[70]

- 612 - Villa Escudero Plantations and Resort. Tiaong, Quezon [71]

- AT-28D

- 137701 - Major Danilo Atienza Air Base, Cavite City, Cavite, Philippines.

- 114645 - Clark Air Base, Angeles City, Pampanga Philippines[72][73]

- 100310 - Edwin Andrews Air Base, Zamboanga City, Philippines.

Taiwan

[edit]- On display

- T-28A

Thailand

[edit]

- On display

- T-28A

- 49-1538 - Prachuap Khiri Khan AFB in Bangkok, Thailand.[75]

- 49-1601 - Don Muang Royal Thai Air Force Base, Bangkok, Thailand.[76]

- 49-1687 - Loei Airport, Loei Province, Thailand.[77]

- 51-3480 - Udorn Royal Thai Air Force Base, Thailand.[78]

- 51-3578 - Chiang Mai AFB, Thailand.[79]

- 51-3740 - Don Muang Royal Thai Air Force Base, Bangkok, Thailand.[80]

- T-28B

- 137661 - Royal Thai Air Force Museum, Bangkok, Thailand.[81]

- 138157 - Royal Thai Air Force Museum, Bangkok, Thailand.[82]

- 138284 - Royal Thai Air Force Museum, Bangkok, Thailand.[83]

- 138302 - Lopburi AFB, Thailand.[84]

- T-28D

- 153652 - National Memorial, Bangkok, Thailand.[85]

United Kingdom

[edit]- On display

- T-28C

- 146289 - Norfolk & Suffolk Aviation Museum, Flixton, The Saints, United Kingdom.[86]

United States

[edit]- On display

- T-28A

- 49-1494 - National Museum of the United States Air Force at Wright-Patterson AFB in Dayton, Ohio. The aircraft is painted as a typical Air Training Command T-28A of the mid-1950s. It was transferred to the museum in September 1965. It is on display in the museum's Cold War Gallery.[87]

- 49-1663 - Hurlburt Field, Florida.[88]

- 49-1679 - Reese AFB, Texas.[89]

- 49-1682 - Laughlin AFB, Texas.[90]

- 49-1689 - Vance AFB, Oklahoma.[91]

- 49-1695 - Randolph AFB, Texas.[92]

- 50-0300 - Dakota Territory Air Museum, Minot, North Dakota.[93]

- 51-3612 - Museum of Aviation, Robins Air Force Base, Warner Robins, Georgia.[94]

- 51-7500 - Olympic Flight Museum, Olympia, Washington.[95]

- T-28B

- 137702 - Air Force Flight Test Center Museum, Edwards AFB, California.[96]

- 137749 - Hill Aerospace Museum, Hill Air Force Base, Utah

- 137796 - Naval Air Station Anacostia, Washington, DC.[97]

- 138144 - Naval Air Station Whiting Field, Florida.[98]

- 138164 - Actively flying and performing in airshows with the Trojan Phlyers in Dallas, TX.[99]

- 138192 - Aviation Heritage Center of Wisconsin, Sheboygan Memorial Airport, Sheboygan, WI[100]

- 138247 - War Eagles Air Museum in Santa Teresa, New Mexico.[101]

- 138263 - Actively flying and based at KRLD Richland Airport, Richland, WA[102]

- 138311 - Air Heritage Aviation Museum in Beaver Falls, Pennsylvania[103]

- 138326 - National Naval Aviation Museum, Naval Air Station Pensacola, Florida[104]

- 138339 - Owned by Skydoc 1989–present (2019) Springfield, Illinois performing with the Trojan Horsemen 2003–2017, and Trojan Thunder 2017–present.[105]

- 138349 - USS Hornet Air and Space Museum Alameda, California[106]

- 138353 - on a pole at Milton, Florida.[107]

- 140047 - Actively flying and performing in airshows with the Trojan Phlyers in Dallas, TX.[99]

- 140048 - National Museum of the United States Air Force at Wright-Patterson AFB in Dayton, Ohio.[108]

- T-28C

- 138245 - WarBird Museum of Virginia in Chesterfield, Virginia.[109]

- 140451 - Middleton Field in Evergreen, Alabama

- 140454 - Battleship Cove in Fall River, Massachusetts.[110]

- 140481 - Pima Air & Space Museum adjacent to Davis-Monthan AFB in Tucson, Arizona.[111]

- 140557 - Naval Air Station Wildwood Aviation Museum, Cape May Airport, Rio Grande, New Jersey.[112]

- 140659 - Southern Museum of Flight, Birmingham, Alabama.[113]

- YAT-28E

- 0-13786 - Private collection, Port Hueneme, California. One of two surviving air-frames, currently in storage awaiting restoration.[114]

Specifications (T-28D)

[edit]Data from Encyclopedia of World Military Aircraft[115]

General characteristics

- Crew: 2

- Length: 33 ft 0 in (10.06 m)

- Wingspan: 40 ft 1 in (12.22 m)

- Height: 12 ft 8 in (3.86 m)

- Wing area: 268.0 sq ft (24.90 m2)

- Aspect ratio: 6.0:1

- Empty weight: 6,424 lb (2,914 kg) (equipped)

- Max takeoff weight: 8,500 lb (3,856 kg)

- Powerplant: 1 × Wright R-1820-86 Cyclone 9-cylinder air-cooled radial engine, 1,425 hp (1,063 kW)

Performance

- Maximum speed: 343 mph (552 km/h, 298 kn) at 10,000 ft (3,000 m)

- Ferry range: 1,060 mi (1,710 km, 920 nmi)

- Service ceiling: 35,500 ft (10,800 m)

- Rate of climb: 3,540 ft/min (18.0 m/s)

Armament

- Hardpoints: 6 with a capacity of 1,200 lb (540 kg) total

See also

[edit]Related development

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

Related lists

- List of United States Navy aircraft designations (pre-1962)

- List of military aircraft of the United States

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ "Historical Listings: Philippines, (PHL)". worldairforces.com. Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 19 May 2011.

- ^ "T-28 Trainer Now at Eglin – Is Latest Word In Instructional Craft". Playground News. Vol. 5, no. 21. Fort Walton, FL. 22 June 1950. p. 10.

- ^ a b The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Aircraft 1985, p. 2678.

- ^ "The Diamond Anniversary Decade, 1981-1990, Part 11" (PDF). Naval Heritage and History Command. p. 342. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 June 2010. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

- ^ Toperczer 2001, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Toperczer 2015, pp. 18–19.

- ^ a b "Đoàn bay 919: Hành trình chinh phục bầu trời". Spirit Vietnam Airlines (in Vietnamese). 2 May 2024. Retrieved 30 November 2024.

Đặc biệt, sự kiện ngày 15/2/1964 đã đánh dấu trận thắng lợi trên không đầu tiên của Đoàn bay 919. Phi công Nguyễn Văn Ba, một trong hai phi công điều khiển máy bay T-28 xuất kích từ sân bay Gia Lâm, đã tiếp cận và tiêu diệt gọn máy bay C-123 chở biệt kích Mỹ.

[In particular, the event on February 15, 1964 marked the first aerial victory of the Flight Crew 919. Pilot Nguyen Van Ba, one of two pilots controlling the T-28 aircraft taking off from Gia Lam airport, approached and completely destroyed the C-123 aircraft carrying American commandos.] - ^ Hobson 2001, p. 12.

- ^ Holm, Richard L. (Winter 1999–2000). "A Plane Crash, Rescue, and Recovery - A Close Call in Africa". Center for the Study of Intelligence, Historical Perspectives. Washington, D.C.: Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on 24 May 2011.

- ^ Leeker, Dr Joe F. (24 August 2015). "Khmer Air Force T-28s (maintained under the supervision of Air America's LMAT, Phnom Penh)" (PDF). library.utdallas.edu.

- ^ "20 DIE IN BOMBING AIMED AT LON NOL". The New York Times. New York, NY. 18 March 1973. p. 1.

- ^ a b c d Ganivet, Jean-Luc. "T-28 Fennec History". fennec.pfiquet.be. Archived from the original on 1 November 2013. Retrieved 31 December 2013.

- ^ Hagedorn 1993, p. 41

- ^ Hagedorn 1993, pp. 42–43

- ^ Godfrey, Joe (16 April 2003). "Profiles: Charlie Summers". AVweb. Archived from the original on 14 June 2012. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- ^ "T-28 Instrumented Research Aircraft". Institute of Atmospheric Science at South Dakota School of Mines & Technology. Archived from the original on 1 January 2012. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- ^ "Next-generation Storm-penetrating Aircraft" (PDF). Institute of Atmospheric Science at South Dakota School of Mines and Technology. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 November 2013. Retrieved 14 December 2013.

- ^ Rogoway, Tyler. "The Storm Chasing A-10 Thunderhog Program Is Officially Dead, Jet To Be Returned To USAF". The Warzone. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- ^ Meier, Sid; Noonan, Jennifer Lee (2020). Sid Meier's memoir! a life in computer games (First ed.). New York: W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-1324005872.

- ^ See German Wikipedia Flugplatz Albstadt-Degerfeld

- ^ Ginter 1981, p. 6

- ^ a b c Darke 2013, p. 147

- ^ Ginter 1981, p. 27

- ^ Ginter 1981, p. 53

- ^ Sweeney, Richard L. (December 1961). "New Role for Nomad". Flying Magazine.

- ^ a b c d Concannon, Milt. "The Lost (and last) Nomad". courteseyaircraft.com. Archived from the original on 1 January 2014. Retrieved 31 December 2013.

- ^ Trichter, J. Gary (12 August 2016). "The Poor Man's P-51: The T-28 Trojan". Retrieved 12 July 2019.

- ^ "The Ejection Site: Stanley YANKEE Extraction System". ejectionsite.com.

- ^ Tate Air Enthusiast May/June 1999, pp. 58–59.

- ^ "Warbirds of New Smyrna, Page 4". angelfire.com. Retrieved 31 December 2013.

- ^ a b c d Renaud, Patrick-Charles. "T-28 Fennec: des ailes pour un renard". aerostories.free.fr (in French). Retrieved 31 December 2013.

- ^ "North American T-28 Trojan/Fennec". amilarg.com.ar.

- ^ a b c d "No. 1040. Hamilton T-28-R2 Nomair (N9106Z c/n 10)". 1000aircraftphotos.com. Retrieved 31 December 2013.

- ^ a b Flying Magazine, April 1962, p. 3.

- ^ Troung, Albert Grandolini; Cooper, Tom (13 November 2003). "Laos, 1948-1989; Part 1". acig.org. Archived from the original on 1 May 2012. Retrieved 17 April 2012.

- ^ Troung, Albert Grandolini; Cooper, Tom (13 November 2003). "Laos, 1948-1989; Part 2". acig.org. Archived from the original on 1 May 2012. Retrieved 17 April 2012.

- ^ Ay, Carlos. "The Illustrated Catalogue to Argentine Air Force Aircraft." Aeromilitaria, 15 August 2013. Retrieved: 31 December 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Taylor and Munson 1973, p. 179.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Krivinyi 1977, p. 178.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Fitzsimons 1988, p. 137.

- ^ Andrade 1982, p. 28.

- ^ Air-Britain Aeromilitaria, March 2015

- ^ Wieland, William A. "Memorandum From the Director of the Office of Middle American Affairs." latinamericanstudies.org, August 1958. Retrieved: 21 February 2010.

- ^ Hagedorn 1993, pp. 22, 27

- ^ Hagedorn 1993, p. 27

- ^ Valero, Jose Ramon. "Picture of the North American T-28 Trojan aircraft." airliners.net, October 2003. Retrieved: 21 February 2010.

- ^ Andrade 1982, p. 56.

- ^ Andrade 1982, p. 58.

- ^ Andrade 1982, p. 62.

- ^ a b Andrade 1982, p. 97.

- ^ Green 1956, p. 238.

- ^ Thompson, Paul North American T-28D Trojan J-HangarSpace Retrieved August 18, 2017

- ^ Andrade 1982, p. 146.

- ^ Andrade 1982, p. 156.

- ^ Andrade 1982, p. 181.

- ^ https://web.archive.org/web/20140108132237/http://www.flightglobal.com/pdfarchive/view/1987/1987%20-%202528.html

- ^ Andrade 1982, p. 143.

- ^ Cooper 2017, p. 14

- ^ Andrade 1982, p. 223.

- ^ Pocock 1986, p. 115.

- ^ "Talking Paper for Chief of Staff, U.S. Army: Guidance for T-28 Aircraft Operations." U.S. Army, 9 March 1964.

- ^ Andrade 1982, p. 336.

- ^ Secrets of US Air Operations in North Vietnam (Bí mật các chiến dịch không kích của Mỹ vào Bắc Việt Nam (in Vietnamese)). Hanoi: People's Police Publisher, p. 513.

- ^ Ginter 1981, p. 22.

- ^ Aviacion Militar Argentina (Amilarg)- North American T-28A/F/P Trojan/Fennec (retrieved 2014-11-23) Archived 2014-11-29 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Museo de la Aviacion Naval - ARA 25 de MAYO - T-28 Fennec (retrieved 2014-08-19) Archived 2008-10-04 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "T-28 Trojan/49-1583." Warbird Registry. Retrieved: 11 June 2012.

- ^ https://www.gluseum.com/AU/Toowoomba/287406544649061/T-28-Trojan-50-221-%22Littl-Juggs%22

- ^ "Skippyscage photography - Philippine Air Force Museum, Manila, Philippines - February 2010".

- ^ "The T-28 Trojan is Not the Tora Tora Plane". 2 December 2023.

- ^ "17712 - North American T-28A Trojan in Philippines - Air Force, Buzu". JetPhotos.

- ^ "645 North American T-28 Trojan Philippine Air Force". 21 March 2012.

- ^ "North American aviation photos - Serial #: 114". JetPhotos.

- ^ "T-28 Trojan/51-3664." Warbird Registry. Retrieved: 11 June 2012.

- ^ "T-28 Trojan/49-1538." Warbird Registry. Retrieved: 11 June 2012.

- ^ "T-28 Trojan/49-1601." Warbird Registry. Retrieved: 11 June 2012.

- ^ "T-28 Trojan/49-1687." Warbird Registry. Retrieved: 11 June 2012.

- ^ "T-28 Trojan/51-3480." Warbird Registry. Retrieved: 11 June 2012.

- ^ "T-28 Trojan/51-3578." Warbird Registry. Retrieved: 11 June 2012.

- ^ "T-28 Trojan/51-3740." Warbird Registry. Retrieved: 11 June 2012.

- ^ "T-28 Trojan/137661." Warbird Registry. Retrieved: 11 June 2012.

- ^ "T-28 Trojan/138157." Warbird Registry. Retrieved: 11 June 2012.

- ^ "T-28 Trojan/138284." Warbird Registry. Retrieved: 11 June 2012.

- ^ "T-28 Trojan/138302." Warbird Registry. Retrieved: 11 June 2012.

- ^ "T-28 Trojan/153652" Warbird Registry. Retrieved: 11 June 2012.

- ^ "T-28 Trojan/146289." Warbird Registry. Retrieved: 11 June 2012.

- ^ "T-28 Trojan/49-1494." Warbird Registry. Retrieved: 11 June 2012.

- ^ "T-28 Trojan/49-1663." Warbird Registry. Retrieved: 11 June 2012.

- ^ "T-28 Trojan/49-1679." Warbird Registry. Retrieved: 11 June 2012.

- ^ "T-28 Trojan/49-1682." Warbird Registry. Retrieved: 11 June 2012.

- ^ "T-28 Trojan/49-1689." Warbird Registry. Retrieved: 11 June 2012.

- ^ "T-28 Trojan/49-1695." Warbird Registry. Retrieved: 11 June 2012.

- ^ "T-28 Trojan/50-0300." Warbird Registry. Retrieved: 11 June 2012.

- ^ "T-28 Trojan/51-3612." Warbird Registry. Retrieved: 11 June 2012.

- ^ "T-28 Trojan/51-7500." Warbird Registry. Retrieved: 11 June 2012.

- ^ "T-28 Trojan/137702." Warbird Registry. Retrieved: 11 June 2012.

- ^ "T-28 Trojan/137796." Warbird Registry. Retrieved: 11 June 2012.

- ^ "T-28 Trojan/138144." Warbird Registry. Retrieved: 11 June 2012.

- ^ a b "Trojan Phlyer's T28s".

- ^ "US Navy and US Marine Corps BuNos--Third Series (135774 to 140052)". www.joebaugher.com. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- ^ "T-28 Trojan/138247." Warbird Registry. Retrieved: 11 June 2012.

- ^ "N63NA (1955 NORTH AMERICAN T-28B owned by URBAN SCOTT J) Aircraft Registration".

- ^ "NORTH AMERICAN T-28 TROJAN" Retrieved: 26 February 2024.

- ^ < "Aircraft on Display: T-28."[permanent dead link] Naval Aviation Museum. Retrieved: 31 December 2013.

- ^ "T-28 Trojan/138339." trojanhorsemen.com. Retrieved: 22 March 2013.

- ^ "Aircraft on Display - USS Hornet Museum". 9 December 2015.

- ^ "T-28 Trojan/138353." Warbird Registry. Retrieved: 11 June 2012.

- ^ "T-28 Trojan/140048." Warbird Registry. Retrieved: 11 June 2012.

- ^ "WarBird Museum of Virginia". warbirdmuseumva.org. Archived from the original on 5 August 2020. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ^ "T-28 Trojan/140454." Warbird Registry. Retrieved: 11 June 2012.

- ^ "T-28 Trojan/140481." Warbird Registry. Retrieved: 11 June 2012.

- ^ "T-28 Trojan/140557." Warbird Registry. Retrieved: 11 June 2012.

- ^ "T-28 Trojan/140659." Warbird Registry. Retrieved: 11 June 2012.

- ^ "YAT-28E". Helen Murphy. Archived from the original on 3 February 2020. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ^ Donald and Lake 1996, p. 333

Bibliography

[edit]- Andrade, John. Militair 1982. London: Aviation Press Limited, 1982. ISBN 0-907898-01-7.

- Avery, Norm. North American Aircraft: 1934–1998, Volume 1. Santa Ana, California: Narkiewicz-Thompson, 1998. ISBN 0-913322-05-9.

- Compton, Frank. "November 79 Zulu: the Story of the North American Nomad". Sport Aviation, June 1983.

- Cooper, Tom (2017). Hot Skies Over Yemen, Volume 1: Aerial Warfare Over the South Arabian Peninsula, 1962-1994. Solihull, UK: Helion & Company Publishing. ISBN 978-1-912174-23-2.

- Darke, Stephen M. (Winter 2013). "The North American T-28D". Air-Britain Aeromilitaria. Vol. 39, no. 156. pp. 147–155. ISSN 0262-8791.

- Donald, David and Lake, Jon. Encyclopedia of World Military Aircraft. London:Aerospace Publishing, 1996. ISBN 1-874023-95-6.

- Fitzsimons, Bernie. The Defenders: A Comprehensive Guide to Warplanes of the USA. London: Aerospace Publishing, 1988. ISBN 0-8317-2181-2.

- Ginter, Steve (1981). North American T-28 Trojan. Naval Fighters. Vol. 5 (First ed.). California, United States: Ginter Books. ISBN 0-942612-05-1.

- Green, William. Observers Aircraft, 1956. London: Frederick Warne Publishing, 1956.

- Hagedorn, Daniel P. (1993). Central American and Caribbean Air Forces. Tonbridge, Kent, UK: Air-Britain (Historians) Ltd. ISBN 0-85130-210-6.

- Hellström, Leif (Autumn 2014). "T-28s in the Congo – Part 1: Stemming The Rebellion". Air-Britain Aeromilitaria. Vol. 40, no. 159. pp. 117–128. ISSN 0262-8791.

- Hellström, Leif (Winter 2014). "T-28s in the Congo – Part 2: Heyday of the Trojan". Air-Britain Aeromilitaria. Vol. 40, no. 160. pp. 147–157. ISSN 0262-8791.

- Hellström, Leif (Spring 2015). "T-28s in the Congo – Part 3: The Twilight Years". Air-Britain Aeromilitaria. Vol. 41, no. 161. pp. 4–17. ISSN 0262-8791.

- Hobson, Chris. Vietnam Air Losses, USAF/Navy/Marine, Fixed Wing Aircraft Losses in Southeast 1961–1973. North Branch, Minnesota: Specialty Press, 2001. ISBN 1-85780-115-6.

- The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Aircraft (Part Work 1982–1985). London: Orbis Publishing, 1985.

- Krivinyi, Nikolaus. World Military Aviation. New York: Arco Publishing Company, 1977. ISBN 0-668-04348-2.

- Pocock, Chris. "Thailand Hones its Air Forces". Air International, Vol. 31, No. 3, September 1986. pp. 113–121, 168. ISSN 0306-5634.

- Tate, Jess. "Ultimate Trojan: North American's YAT-28E Project". Air Enthusiast, No. 99, May/June 1999. pp. 58–59. ISSN 0143-5450.

- Taylor, John J.H. and Kenneth Munson.Jane's Pocket Book of Major Combat Aircraft. New York: Collier Books, 1973. ISBN 0-7232-3697-6.

- Thompson, Kevin. North American Aircraft: 1934–1998 Volume 2. Santa Ana, California: Narkiewicz-Thompson, 1999. ISBN 0-913322-06-7.

- Toperczer, Istvan. MiG-17 and MiG-19 Units of the Vietnam War. London: Osprey Publishing Limited, 2001. ISBN 1-84176-162-1.

- Toperczer, Istvan, MiG Aces of the Vietnam War, Schiffer Publishing, Ltd., 2015; ISBN 978-0-7643-4895-2.

- United States Air Force Museum Guidebook. Wright-Patterson AFB, Ohio: Air Force Museum Foundation, 1975.

Further reading

[edit]- Adcock, Al. T-28 Trojan in Action. Squadron/Signal Publications Inc. 1989. ISBN 0-89747-211-X

- Cupido, Joe., "Veteran United: A T-28D Trojan Meets Up with a Former Pilot." Air Enthusiast, No. 83, September/October 1999, pp. 16–20 ISSN 0143-5450

- Genat, Robert. "Final Tour of Duty - North American's T-28 Trojans". North Branch, Minnesota: Specialty Press, 1996. ISBN 0-933424-61-2

- Núñez Padin, Jorge Felix (2010). Núñez Padin, Jorge Felix (ed.). North American T-28 Fennec. Serie Aeronaval (in Spanish). Vol. 28. Bahía Blanca, Argentina: Fuerzas Aeronavales. ISBN 978-987-1682-02-7.

External links

[edit]- North American T-28B Trojan – National Museum of the United States Air Force

- Warbird Alley: T-28 page

- T-28 FENNEC : History + 2006 inventory Archived 21 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- T-28 Trojan Registry: The histories of those aircraft that survived military service

- North American T-28 Trojan (Variants/Other Names: AT-28; Fennec)